Creating Work Sessions that Work

Collaboration sounds great—until someone schedules another aimless “brainstorming” meeting. Bringing diverse people together can unleash their collective powers, but it takes more than a white board and Post-its. While there are many ways to approach a collaborative session, a few key elements are critical to making it productive. Whether working with creatives, business stakeholders, or users, learning the essential elements of designing collaborative meetings will ensure the outcome is actionable, and not just another time waster.

UX teams know the value of collaboration, though the first step to creating productive meetings is understanding that not every challenge warrants a group work session. An engaging and effective collaboration session requires more investment from the planner and the participants. Discussions about project updates or communications for awareness are best left to emails, short stand-ups, or spur-of-the-moment conversations. However, when there’s a meaty challenge or problem to solve, designing an interactive meeting with cross-functional teams can lead to faster action and better outcomes. Situations that require input and consensus from diverse groups or a greater sense of ownership—whether it’s a new website or strategic planning—are the ones that will most benefit from investing in a collaborative session.

Effective collaboration means allowing for time to plan, people to participate, and energy to engage, but returns ideas, ownership, and action. Invest more when a team needs to get more. In this article, we’ll take a look at how to design an effective, collaborative meeting.

Select the right method

Collaboration methods and exercises are as vast and diverse as user research. Deciding what approach to use can be guided by answering two questions:

- What is the problem or challenge that needs to be solved?

- What results does the meeting need to produce?

To get started, articulate the goal and what needs to be accomplished by the end of the session. The ideal outcome drives the format for exercises. Every situation dictates a different approach and a session may even benefit from combining multiple collaboration methods. Here is a progressive example to illustrate how the meeting methods could vary with a few different challenges.

Note: For the purposes of this article, these examples focus on content. However, they are just as appropriate for identifying audience objectives, setting goals as a team, and many other possible challenges.

Challenge: “We need different ideas for new content fast.”

Method and result: A post-up brainstorming session will produce many ideas in a short time frame. (See the related tip below.)

Challenge: “We have a pile of new content ideas and no clear direction.”

Method and result: Affinity mapping can be used to group and categorize ideas and see common themes.

Challenge: “We have several content themes but no consensus on what to produce first.”

Method and result: Forced ranking helps participants agree on priorities by creating a single ranked list of items from a group.

Challenge: “Our last content planning project went really poorly.”

Method and result: Unlike a debrief, a premortem assess a team’s concerns when a project begins to formulate an action plan before things go awry.

The meeting approach should use the best method to achieve the desired results. The many types of methods and possible exercises are too extensive to cover in one article. For more suggestions like the examples above, the book Gamestormingoffers great ideas for methods (games) classified by objective.

A tip for ideation sessions: Don’t open without closing

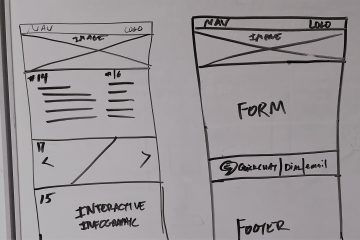

Brainstorming gets a bad wrap because it often goes nowhere. Ideation exercises should combine activities that allow for diverging (opening) and converging (closing). Diverging is how participants consider the possibilities of how to address a challenge. It encourages people to generate as many ideas as possible. Converging is how a direction or solution is selected from a narrowed set. The converging stage, or closing, is necessary to move forward with anything from the diverging stage. For example, if the team is asked to create a landing page for a campaign, they might diverge through rapid sketching to generate a wide range of ideas. Discussing and combining ideas will converge the group’s thinking and dot voting can lead to a clear consensus on the best approach.

Participants: Who and how many

Who to invite and how many participants will vary with every situation and is another factor to consider during method selection. Smaller numbers (5-10) of cross-functional participants allows for diverse thinking without being too overwhelming to manage. That doesn’t mean that sessions with many more people can’t be productive—it just means planning for splitting people into smaller teams and having a large enough area to handle break-out sessions where people can have their own space to work and talk. Whenever possible, plan pairings or teams in advance and always have a backup plan in case someone drops out at the last minute. When running sessions where the participants are strangers, glean as much as possible about them (departments, titles, experience levels) to avoid partnering the dynamic duo who always work together or asking executives in a power struggle to buddy up.

Numbers aren’t critical to success. What is critical, is having participants with mutual respect for one another and a willingness to trust and engage. Collaboration requires comfort and to some degree an organizational culture that says sharing and exploring is okay in a safe space.

Add focus, structure, and constraints

Once the session approach has been determined, based on the challenge and participants, it’s time to add some structure to both the problem, and the work itself. First, the problem: for participants to effectively contribute to a solution, they must understand the real problem. The session facilitator can’t assume everyone knows what the challenge is and why they’ve been brought together, or they risk miscommunications between team members.

With this in mind, a well-crafted, targeted problem statement is critical to directing teams’ focus. At the beginning of the session, the challenge and goal must be articulated to establish a shared understanding. The trick is to keep it simple and not guide the solution. For example, when design-firm IDEO wanted to invent a product that would allow cyclists to carry and drink coffee when riding, the challenge wasn’t presented to participants as “design a bicycle cup holder” but as “help bike commuters to drink coffee without spilling it or burning their tongues.” The objective is focused, but does not dictate the solution. A single targeted question or problem also helps people to concentrate their ideas. Write the challenge on a whiteboard or worksheet to keep the goal top-of-mind for participants during the meeting. Group sessions can get easily derailed, and a well-framed challenge will help keep everyone moving in the same direction.

To free people up to exchange ideas, there also needs to be structure in the meeting. It may seem counter-intuitive, but without rules, productive collaboration among diverse participants in an organization won’t happen. Group dynamics, politics and personalities will interfere. HIPPOs (highest paid person’s opinion) will dominate, negative Nancys will suck energy, or rambling de-railers will head down rabbit holes—all of which limit a group’s potential. Planned collaborations need to balance power and communication styles. Establish ground rules that encourage respect and collaboration, set time constraints, and diversify activities to suit introverts and extroverts. Segment sessions into timed activities with silent ideation and then discussion, and dictate basic guidelines for when to talk and listen, so everyone has a voice.

Most meetings can also benefit from assigning people in the key roles of leader, note-taker, time-keeper, and facilitator. Depending on the session and exercises, all these roles might not be applicable, but a non-participating facilitator to guide things is ideal. This person can watch the clock and keep an ear to conversations. A good facilitator will help groups maintain focus to successfully reach the goal.

Preparation and pace: Timing is the hardest thing and everything

The meeting length should be based on the participants’ availability and the session’s goal. Exercises need to be designed with constraints in mind: what’s realistic to accomplish during the allotted time, with the number of attendees?

People with user research experience should draw on their planning skills and create a facilitator’s script with instructions, a minute-by minute agenda with tasks and breaks, and a checklist for preparations. Getting the pace and timing right is something learned through observing and experimenting. Even seasoned pros sometimes need to deviate from the plan and improvise. The most common, avoidable novice mistakes are:

- Trying to do too much in one session or including too many complicated activities.

- Realizing there isn’t enough time left to reach the goal but not reacting and adapting.

- Not spending enough time preparing for the session itself.

Addressing the last point is critical to success. Jared Spool, who has researched how design teams successfully collaborate, observed the following:

The more effective teams spent more time preparing for the meeting than the less effective teams. In setting up the meeting, they’d discuss the approach they’d use and exactly what they wanted to get out.

The teams that didn’t spend time enough time preparing just fell into their “old, familiar patterns that prevented things from moving forward.”

When the day arrives

Plan to be prepared, but be prepared for the unexpected. Last minute participant cancellations and exercises interrupted by urgent texts will happen. It helps to have an extra team member ready to jump in as a substitute or a session “runner” to help with the unexpected. Control and prep what you can in advance: the room, supplies, name tags, hand-outs. Create an inventory list and have everything packed and ready. It’s one less thing to worry about the day of the session.

The room set-up should facilitate collaboration. There’s a reason that colored Post-its, index cards, sketch templates, poster-sized stickies, and white boards are loved by UXers everywhere. Flexible tools and workspaces inspire open thinking. To ideate, share, and synthesize information, people need to create things and then have a space in which to see and organize them. Mobile information “pieces” on tables, walls, or virtual boards, allow for replacing, moving and sorting while people explore ideas.

Unless innovation and product design is the life of the business, most companies don’t have fantastic collaboration areas available like IDEO and Frog. Luckily, even the drabbest, most ill-equipped conference room can be transformed with inexpensive supplies. I have a UX suitcase always stocked with supplies and toys for workshops. What I pack depends upon the participants and the exercises I’ve designed, but my ready-to-go travel stash means never having to run out the night before in search of magnetic hot-pink memos, double-sided tape, and smiley face stickers. Always be prepared!

Takeaways

UX leads or teams who want to create something new or do something better shouldn’t just spend more time designing solutions—but instead designing the collaboration needed to get there. Planning collaborative sessions will result in better outcomes.

For more on this topic and the sources mentioned check out:

- Dan Brown’s book, Designing Together: The collaboration and conflict management handbook for creative professionals, teaches designers how to better collaborate and navigate difficult situations within creative teams.

- David Gray, Sunni Brown, and James Macanufo’s book, Gamestorming: A Playbook for Innovators, Rulebreakers, and Changemakers is a great resource for finding the right activity for working better together.

- Kick Ass Kickoff Meetings, by Kevin Hoffman, sees every meeting as an opportunity–and provides guidelines on how not to waste it.

- IDEO’s Design Thinking Toolkit is a free, downloadable step-by-step guide to solving human-centered design problems.

- Perspectives over Power, Habits of Collaborative Team Meetings, by Jared Spool, looks at what prevents teams from producing the best designs and how to overcome it.